In terms of bilateral trade volume, China and Japan had the world’s largest trading relationship in 2014. Moreover, Japan is the biggest source of direct foreign investment in China, even ahead of the US. Nevertheless, China’s remembrance of Japanese war crimes perpetrated on Chinese soil during World War II continues to mar their bilateral relations. A territorial conflict over the uninhabited Senkaku (Chinese: “Diaoyu”) islets, which are under Japanese administration, routinely gives rise to anti-Japanese demonstrations in China. But aside from these emotional issues, the role of concrete security interests in this relationship ought not to be underestimated. So what are China’s security interests and strategic objectives, and in what way are they affected by Japan and its status as America’s most important ally in East Asia?

China’s main strategic objectives

Most observers work on the assumption that the key strategic priorities of the Chinese leadership are as follows: (1) to sustain the present political system under the leadership of China’s Communist Party, which means preventing systemic change or the collapse of the state; (2) to preserve China’s territorial integrity while protecting the leadership’s defined “core interests”;1(3) to safeguard the trade routes which are vital to China’s economic development; and (4) to gradually push US forces out of the region, giving China a role of lasting predominance in Asia.

China’s territorial claims, its threat of violence against Taiwan, and its now strongly enhanced maritime presence in the East and South China Seas all potentially conflict with US strategic objectives. In addition, there is the underlying conflict between China’s Leninist state model and the Western ideal of liberal democracy, which China’s Communist Party sees as a political threat. The leadership in Beijing perceives the risk of infiltration, subversion or “disintegration” of the Chinese state by “hostile forces” to be as great as ever, claiming that such forces are working for a “peaceful evolution” in China of the kind that led to the collapse of the Soviet Union. This explains the recent increase in repressive measures against regime critics and “Western values” in general. Also indicative of the leadership’s lack of confidence in the country’s social stability is the fact that, in 2011, the Chinese budget for domestic security exceeded defence spending for the first time ever.

China’s fear of containment

At the same time, Chinese foreign policy reflects concerns about American containment. These concerns were markedly reinforced by Donald Trump’s criticism of China at the start of his US presidency. Even in the preceding years, Chinese security analysts had been pointing to the threat of China’s encirclement by military bases of the US and its allies. By contrast, US security analysts have recently been warning that China is massively expanding its military presence in the Asia-Pacific, as evidenced by paramilitary forces like the so-called “maritime militia”; land reclamation projects; the militarisation of reefs in the South China Sea (with the construction of runways, hangars, and radar installations); and China’s increased military cooperation with partners such as Pakistan and Russia. Such developments would have alarming implications for the security of US allies and military installations in the region, US experts say. Given these starkly contradictory assessments of China’s situation from Beijing and Washington, it seems helpful to take a closer look at the argument from the Chinese perspective.

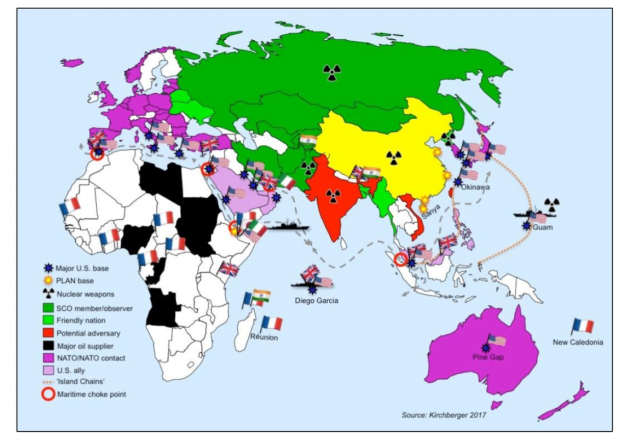

Figure 1: Alliances and military bases in China´s strategic environment

China’s “Malacca dilemma” and the issue of overseas bases

The above map illustrates the strategic environment in which China operates. Plotted in grey are the maritime trade routes that carry more than 80 percent of China’s oil imports and a large share of its commodity exports. The map also shows the maritime choke points that these goods must pass. US allies are marked in purple. China itself has only one formal military alliance at present, namely with North Korea. This relationship is fraught, however. From a Chinese perspective, North Korea, far from being a reliable partner, seems to be a source of strategic uncertainty. The planned deployment of the American THAAD missile defence system in South Korea – officially intended to counter the threat from North Korea – poses a strategic problem to China, whose deterrence strategy is largely based on its missile forces.

Meanwhile, China’s relationship with Russia, which has greatly intensified since the crisis in Ukraine and subsequent Western sanctions against Russia, remains complicated. Sino-Russian relations are partly characterised by strategic cooperation (mainly on raw materials extraction and defence technology) and partly by mistrust and rivalry, especially over the two countries’ roles in Central Asia. Only Pakistan, which has faithfully stood by China for decades, can be considered a reliable partner to Beijing. Cooperation with Islamabad is based on cooperation in defence technology and high Chinese investment in Pakistan’s infrastructure. By contrast, the US maintains a wide military network of long-standing bilateral alliances throughout the Asia-Pacific, to include advanced nations like South Korea, Japan, Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand. Closer military cooperation has developed with other countries in the region, among them India and Vietnam. China, on the other hand, has been the object of a US and EU arms embargo since 1989 in response to its bloody suppression of peaceful protests in Tiananmen Square. This embargo has considerably limited the scope for closer strategic cooperation between China and the US or EU member states, and Chinese officials have routinely criticised it as being disproportionate and as an instrument of Western containment. As a result, China’s arms industry has been forced to spend a lot of time and money on developing its own defence technology. Were it not for this, China’s progress in this area would be even faster than it already is. In comparison with China, countries in the region that cooperate with leading Western partners on defence technology need to mobilise far fewer resources to reach a relatively high level of military development.

For some years now, there has been speculation about a so-called Chinese “string of pearls strategy”, which refers to suspected plans to establish military bases along maritime trade routes. In 2016, after its naval forces had already been deployed to the Horn of Africa for years, China started to build its first naval logistics base in Djibouti. Western media often criticised this move without taking into account that several other nations, in particular France, the US, Italy, and even Japan, had maintained similar bases in Djibouti for years – in Japan’s case since 2011. China’s first overseas base appears even less extraordinary in view of the number and quality of existing Western military bases in Eurasia, Africa, and the Caribbean. The above figure shows a selection of key overseas military bases. For historical reasons, these are primarily bases of the former colonial powers France, Great Britain, and the US. Italy, India, the Netherlands, and Turkey, however, also maintain military bases far away from their homelands. When viewed against the backdrop of China’s enormous share in world trade and its huge investment in large-scale infrastructure projects in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Chinese military presence overseas seems relatively modest.

Impact of the Pax Americana on China’s role in Asia

China, on the other hand, is concerned about the large number of US military bases and monitoring systems along the Korean peninsula and the so-called “first island chain” (Japan, Okinawa, Taiwan, the Philippines), relatively close to population centres on China’s east coast. The shortest distance between China and Taiwan is only 185 kilometres. A key reason for China’s perception of encirclement appears to be the high surveillance capabilities directed from those bases against its armed forces. In 2013, experts at Wuhan Naval University of Engineering urgently warned of the threat from extensive surveillance of Chinese waters by the US and its allies. Through reconnaissance flights, satellite surveillance, and land-based listening posts, the US had almost total real-time coverage of all Chinese naval activities. According to the experts, developing electronic countermeasures for jamming such surveillance capabilities could be life-saving for the Chinese navy.

As US allies, Japan and South Korea play a key role in China’s threat perception owing to their geographic location. Not only are a large number of powerful US military units deployed on their territories, but they, along with Australia, have been granted access to the AEGIS technology by the US. AEGIS is an integrated combat system which provides the naval forces of these countries significant network capabilities and thus an enormous strategic advantage over non-networked forces in air defence and ballistic missiles defence operations. Shared technologies also facilitate military cooperation among US allies. Since they have signed agreements on the exchange of military data, they also have the option to share situation pictures in a conflict. This results in considerable synergy effects, which China endeavours to counter with its own technological developments in fields like anti-satellite technology, powerful sensors, and long-range precision missiles. In 2007, China first demonstrated that it was capable of using a ground-based missile to destroy a satellite in orbit. Such endeavours are accompanied by diplomatic and economic measures aimed at breaking the alliance.

Japan is the most powerful and closest US ally in Asia. Until recently, Japan’s pacifist constitution, with its articles prohibiting arms exports and capping defence spending, confined it to a relatively passive role in relation to China. Japan also showed restraint in terms of strategic cooperation with other countries in the region. However, Japan’s recent efforts to seek closer military cooperation with other regional US allies – among them Australia, India, and the Philippines – is worrying to the Chinese leadership.

Domestic challenges increase pressure on China

The current situation is exacerbated by the fact that the Chinese leadership appears to be facing considerable domestic challenges. These probably stem from a slow-down in economic growth owing to unfavourable demographic developments in an aging society; serious problems on the part of the Communist leadership in making progress on tackling environmental pollution and improving food security; and probable major problems in the Chinese banking system. A sign that the Communist Party’s leadership is now under much greater pressure is the fact that it has recently stepped up repressive measures. These include a clean-up campaign against corrupt senior officials; public exposure of critical bloggers; a crackdown on human rights activists and lawyers; stricter censorship of the media, accompanied by anti-Western propaganda campaigns; electronic surveillance in universities; kidnapping individuals from across Chinese borders; and strict controls on foreign-funded NGOs. These measures are indicative of uncertainty and nervousness, not of strength.

Owing to China’s historically strained relationship with Japan, it is easy for the Communist Party to maintain and foment anti-Japanese sentiment within Chinese society, allowing it to distract public attention from domestic scandals and towards an external opponent. Japan, then, has repeatedly been misused as a target of nationalist protest. The nationwide anti-Japanese riots of 2012 were, at least partly, orchestrated by the government, and coincided almost exactly with legal proceedings against the overthrown top government official, Bo Xilai – a highly embarrassing case for the Communist Party. With such practices, China squanders the chance to improve its relationship with Japan in the interests of their common future and closer economic relations.

Conclusion

A fair assessment of the strategic situation in China requires recognition of China’s legitimate security concerns with regard to Japan and other US allies. However, this should not mean accepting inappropriate and legally untenable Chinese territorial claims, or tolerating aggressive and provocative posturing against peaceful stakeholders in the region.

Dr Sarah Kirchberger is the Head of the Centre for Asia-Pacific Strategy and Security at the Institute for Security Policy of the University of Kiel, Germany. This article reflects the author’s personal opinions.

1 These core interests include the Taiwan issue, the countering of separatist movements in Xinjiang and Tibet, and – according to recent announcements – the defence of China's contested territorial claims in the East and South China Seas.

Copyright: Federal Academy for Security Policy | ISSN 2366-0805 Page 1/4