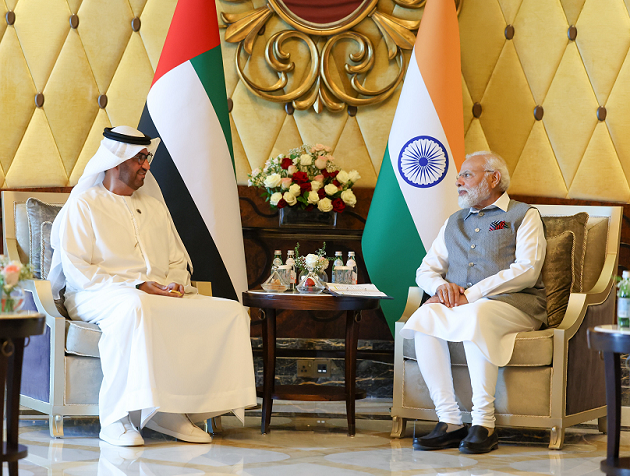

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and COP28 President-designate and CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company Sultan Al Jaber in conversation: India covers around 80 percent of its energy requirements from the Gulf region. Photo: Flickr/MEAphotogallery/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Deed

In early June 2023, German Federal Minister of Defence Boris Pistorius visited India’s capital New Delhi and met with his Indian counterpart Rajnath Singh. At this meeting, Pistorius advocated closer military cooperation with India because it is one of Germany’s most important strategic partners in the Indo-Pacific region. The Federal Minister of Defence even held out the prospect of a military partnership on the same level as Germany’s partnerships with Japan and Australia. Simplified rules already apply to arms deals between Germany and these two Indo-Pacific countries.

For a long time, it would have been hard to imagine India and a member of NATO establishing closer relations like this. During the Cold War, non-aligned India maintained close armaments cooperation with the Soviet Union, while India’s rival Pakistan was one of NATO’s partners. Yet the changed global situation has brought India and the West closer together. In addition to factors such as India’s more confident stance under Narendra Modi’s government and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, shared views on China play a role. In April 2023, India overtook China as the country with the world’s largest population. India now has the fifth largest economy in the world. The simultaneous rise of India and China is not without tension. Beijing has long refused to recognise the Sino-Indian border in the Himalayas and made claims to the territory of the Indian state Arunachal Pradesh. In 2020, for example, as many as 20 Indian military personnel were killed in a border incident in the Galwan Valley.

Samir Saran, a pioneering strategic thinker and President of the Observer Research Foundation in Delhi, got to the heart of India’s security concerns in November 2023: “China wants a multipolar world but a unipolar Asia”. The fact that Saran expressed this opinion at a conference in Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), of all places, was quite symbolic. The profound geopolitical shifts have also caused the UAE and neighbouring Saudi Arabia to rethink their security policy – but in a different way than India’s. For a long time, both countries were probably among the United States’ closest partners in the Middle East. However, since Russia’s attack on Ukraine, if not before, these two Gulf states have made marked adjustments to their security policy. Neither of these two countries joined in the US sanctions against Russia. In light of the hardening fronts in Chinese-American relations, the UAE and Saudi Arabia are increasingly orienting their positions towards a multi-vector style of foreign and security policy primarily driven by their own interests. In summer 2023, BRICS invited both countries – along with Iran, Ethiopia and Egypt – to join the organisation consisting of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. At the same time, the UAE and Saudi Arabia continue to cooperate closely with the West in many areas. India plays an important role in this balancing act by the Gulf states.

India’s relations with the Gulf region

On the margins of the G20 Summit in New Delhi in September 2023, India, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, the US and several EU countries, including Germany, signed a memorandum of understanding for an India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC). The infrastructure project, which will also include projects in Jordan and Israel, calls for two separate corridors – one between the Middle East and Asia, and one between the Middle East and Europe – which will only be fully effective together. It is to include several projects to improve the infrastructure for data communication and for the transport of goods and energy (especially hydrogen) and to make trade between Europe and India up to 40 percent faster. The project, which is said to have a total volume of up to 20 billion euros, can be a seen as a competitor to the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative infrastructure project and the Turkish Development Road Project. The memorandum of understanding includes the expansion of power grids, high-speed data cables and energy pipelines between the Middle East, Asia and Europe, as well as investments in direct rail and shipping connections. According to American media, US President Joe Biden called the project a “really big deal”. The Israel-Palestine conflict flaring up again has, however, at least raised doubts as to whether it will be implemented in the near future, even if key players such as France, the UAE and India have continued to express their commitment to the project. Yet even without the IMEC, relations between the Arab world and India are unlikely to become less important. Even now, their ties are already too close.

According to the World Bank, India’s economy has more than quadrupled in size over the past 20 years. Most recently, its economic growth has been about seven percent per year. By the end of this decade, India could also catch up with Germany and Japan, joining the ranks of the three largest economies in the world. In 2022, the volume of India’s foreign trade with the entire Arab world amounted to some 200 billion US dollars. In 2017, this figure was still around 140 billion. About twelve percent of Indian exports go to the Gulf. However, imports are even more important, especially because the Indian economy urgently needs energy imports in order to maintain its growth. About 80 percent of India’s energy requirements are met by the Gulf region. This increased cooperation began in the late 2010s and follows a long line of historical developments. The history of trade between the Arabian Peninsula and the Indian subcontinent dates back to ancient times and involves one of the oldest trade routes in the world. Their shared history as part of the British colonial empire and the large communities of Indian migrant workers in countries such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Oman and Qatar have since linked the regions even more closely.

The UAE ranks first among India’s trade partners in the Arab world. Despite its small population of only 10 million, the United Arab Emirates is now India’s third most important trade partner overall, with an annual trade volume of around 72 billion euros (2022). In addition, a considerable amount of direct investments flow from the UAE to India; with 3.3 billion US dollars in 2023 alone, the UAE is already the fourth most important foreign investor in the country. The food sector is particularly important in this regard. There are also significant investments in the Indian start-up sector and green technologies. In May 2022, the UAE-India Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) created a new foundation for the countries’ bilateral relations. The agreement integrates the two markets even more closely and considerably reduces customs duties for around 80 percent of all goods. The UAE was one of the first foreign partners to join the Indian United Payments Interface (UPI) digital payment system, through which more than 10 billion transactions were carried out in August 2023 alone.

With a volume of around 42 billion US dollars, Saudi Arabia ranks second among India’s trade partners in the region and fourth among India’s most important trade partners overall. India imports far more from Saudi Arabia than it exports there. In addition, both countries have recently dramatically increased their direct investments. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is investing in a diverse portfolio in India that includes infrastructure and energy projects, agriculture, minerals and mining, as well as the education and health sectors. There has also been a striking increase in Indian investment in Saudi Arabia. The green energy sector has particularly great potential for growth. In November 2023, press reports circulated saying that Saudi Arabia also plans to invest billions in the sports sector and to acquire shares in the Indian cricket league. Under the leadership of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the Kingdom has given high priority to investments in the sports sector and sees them as part of its set of power policy instruments, as is also evident in golf and football.

India’s other important trade partners include Kuwait, Iraq and Qatar. With Qatar, gas exports are of particular importance; a significant amount of India’s gas imports come from this Emirate. However, in autumn 2023, a court in Qatar sentenced eight Indian naval veterans to death, resulting in a diplomatic incident. Little is known about the background of the case. Indian media reports referred to accusations of espionage regarding a Qatari submarine programme and possible disclosure of secrets to Israel. In late December 2023, the death sentences were commuted to long prison sentences through an appeal. In February 2024, the naval veterans were released. A few days earlier, QatarEnergy and Petronet LNG (India) had announced their largest-ever gas deal. From 2028 to 2048, 7.5 million tonnes of liquid petroleum gas are to be delivered to India each year.

In addition to foreign trade, it is worth taking a look at the labour markets in the Gulf states themselves. Today, the more than eight million Indian citizens living in the region work not only in the low-wage sector, such as on construction sites, in the hospitality industry or as drivers and couriers, but also in the high-tech sector, in the financial sector or in executive positions at billion-dollar companies. Furthermore, about 30 percent of all start-ups in Dubai are founded by specialists and executives from India. Accordingly, Indians are responsible for a large part of the Gulf region’s economic power. February 2024 saw yet another demonstration of the importance of these countries’ relations. At the end of his second term, Indian Prime Minister Modi inaugurated a Hindu temple in Abu Dhabi, the largest of its kind in the Middle East. It was Modi’s seventh state visit to the UAE alone. The visit was accompanied by a number of additional cooperation agreements in the areas of digital infrastructure, connectivity, and trade.

India as a new strategic player in the Middle East

As the developments in the course of Russia’s attack on Ukraine have shown, economic policy is always also part of a security policy agenda. Like China, India is making efforts to link economic and security aspects. For example, New Delhi is considerably expanding its activities in the dual-use sector and the IT industry. In addition to new cooperation arrangements between Indian and Israeli companies, the UAE and Saudi Arabia are also among India’s partners in the high-tech industry. In this regard, joint production of semiconductors is just as important as the exchange of information on cybersecurity, as already manifested in a joint memorandum of understanding in 2016. On the Indian side, telecommunications providers and defence companies such as Hindustan Aeronautics Limited are particularly important in this context. Increased cooperation can also be observed in the fields of armament and spaceflight. In 2017, for example, the first Arab nanosatellite was launched into space from Sriharikota, India, and Israeli, Emirati and Indian defence companies are working together to further develop the SPYDER air defence system. At the same time, BEL, an Indian company, is working with partners from Saudi Arabia to develop new guided-missile systems and instruments for unmanned aviation.

These examples show that India is seeking new cooperation with like-minded partners. In this context, it is not only the Gulf states’ geographic location that makes them important for India. New Delhi also sees their new political clout in the region as a special incentive for enhanced partnerships. Since Prime Minister Modi took office, India has been increasingly oriented towards the West. For decades, India had built up its armaments sector primarily with Russian technology and only partly with Western technology, but, since 2016 at the latest, New Delhi has been relying more on military equipment from Western partners. India’s strategic view of the Middle East is also changing. Modi’s security policy adviser Ajit Doval, in particular, is setting a new course in India’s Middle East policy. Since 2015, Doval, who was previously head of the Indian Intelligence Bureau (IB) and is therefore well-connected in the Emirates and Riyadh, has increasingly shifted India’s focus towards the emerging and financially strong Gulf states. As a result, a whole range of memoranda of understanding have been signed in virtually all areas of security policy: They range from Indian-Omani training missions in 2022 and the fight against organised crime in cooperation with the UAE to joint naval exercises in the Arabian Sea.

In terms of international alliances, New Delhi’s approach is based on a broader agenda than before. First of all, this means creating its own initiatives and forums in order to exert political and security influence without interference by other competitors, for example in the expansion of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA). In this organisation, India has the opportunity to establish direct contact with almost all countries bordering the Indian Ocean and to put forward economic and political initiatives. Secondly, on a global level, India is focusing on participating in forms of international cooperation shaped by other countries. For example, India is a member of the Sino-Russian-dominated Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and the BRICS countries, but is also increasingly involved in a number of more Western forums such as the G7 or the IMF.

India as an ambivalent partner for Europe

Not only is India confidently exploring new foreign and economic policy avenues under Modi’s government, but US, French and German overtures, especially against the backdrop of China’s rise, mean that India is gaining more alternatives to its old partners or competitors. As a result of these new political conditions, new forms of cooperation have emerged over the past few years, such as the I2U2 group, in which Israel, India, the United Arab Emirates and the United States participate and which decided on greater cooperation in the fields of energy, water infrastructure and food security as of 2022.

India’s new armaments cooperation arrangements with a number of Western states as well as Israel, the UAE and Saudi Arabia also show that, at least in the current situation, New Delhi has certainly understood that, on its own, it has little chance against its rival China. Nonetheless, India’s new foreign and security policy should not be understood as a definitive commitment to the pro-Western camp. After all, India continues to make investments from Iran to Russia within the scope of its North-South Transport Corridor (NSTC) and regularly takes positions within the United Nations that are contrary to the Western ones. Instead, India’s activities, like those of the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, should be seen as confident, primarily driven by national interests and therefore also ambivalent with regard to partners. Commitment to static alliances is not one of the preferred instruments in Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar’s foreign policy toolkit, which instead focuses on values such as autonomy, nonalignment, resilience and independence.

This results in new opportunities and challenges, especially for German and European players. New cooperation can be established at both the economic and security policy levels as an alternative to China. Germany’s level of technological development continues to be of great interest to companies from India and/or the Gulf region. European companies can develop new synergies in cooperation with partners from the Gulf region and/or India, especially in the area of energy transition. In particular, this will require a financial and economic policy framework in the form of start-up funding, contingency insurance and guarantees to enable European companies to accept the risks involved in the investments. Various discussion forums and conferences have shown that partners in the Gulf region and India greatly welcome such efforts. In addition, European institutes and scientific institutions have accumulated considerable knowledge regarding management of climate change, which remains relevant for the Gulf region and India since they are particularly threatened by it, even though both regions have made considerable scientific advances in climate research. Within the next two decades, both regions will have to deal with massive water shortages, extreme weather conditions and continuously high temperatures that regularly reach over 50°C.

However, European and especially German players could have the greatest leverage through strengthening connections in the form of new economic corridors by land and sea. This includes not only the development of new port and infrastructure projects, but also the maintenance of existing trade routes. The Houthi rebels’ attacks on international shipping in the Gulf of Aden show how quickly restriction of important trade corridors can affect the economies of India and Europe. As major export countries, India and Germany have a real interest in establishing new security missions, especially at sea.

At the same time, European and German players also have great potential for cooperation in other areas, especially with India. Existing structures in the educational and cultural sectors, for example, should be expanded and reinforced. Because both India and Germany see themselves as democratic states, expanding civil society relations is an important basis for sustainable ties between the two countries. Nevertheless, risks such as increasing religious-nationalist tendencies under Modi, which have – according to organizations such as Freedom House - already had a negative impact on the quality of Indian democracy and could have more extensive effects, must also be taken into account. India, for its part, often calls for a less patronising attitude from its Western partners. Accordingly, New Delhi’s newfound confidence can be expected to influence the flow of bilateral conversations on such matters.

Visits by Federal Minister of Economic Affairs Habeck and Federal Chancellor Scholz have made it particularly clear that Germany is in a much weaker economic policy position in India and the Gulf region than it was even a few years ago. This became especially evident in the recent negotiations with the Gulf states in which the German side had to accept contracts with significantly longer contractual periods and more expensive conditions. What is more, concerns regarding the human rights situation in India and partner countries in the Gulf region may also play a role for German policy makers. In terms of Germany’s security policy, however, expansion of cooperation with India and the Gulf states could serve as a further building block in a forward-looking approach to an increasingly multipolar world order. Particularly, if Europe does not want Russia or China to fill the void and gain more influence in the region. For this purpose, it is absolutely necessary to conduct a thorough analysis of the interests and political priorities of India and the Gulf states and compare them with our own interests and values.

Stefan Lukas is Managing Director of Middle East Minds and guest lecturer at the Bundeswehr Command and Staff College. Leo Wigger is associate partner responsible for South Asia and Eurasia at the Candid Foundation and a member of the editorial board of Zenith, a magazine covering the Middle East. This article reflects the authors’ personal opinions.

All issues of the Security Policy Working Papers are available at:

www.baks.bund.de/en/service/arbeitspapiere-sicherheitspolitik